- Home

- Walter J. Ciszek

With God in Russia

With God in Russia Read online

Contents

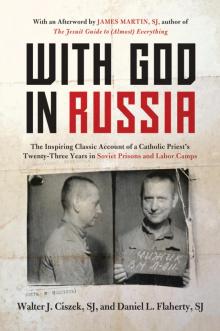

COVER

TITLE PAGE

INTRODUCTION: The Story Behind the Story

CHAPTER 1: The Beginnings

CHAPTER 2: Moscow Prison Years

CHAPTER 3: In the Prison Camps of Norilsk

CHAPTER 4: A Free Man, Restricted

CHAPTER 5: My Return Home

AFTERWORD: The Sign of the Cross

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Introduction

The Story Behind the Story

I WAS ASSIGNED to America magazine in June 1962, the year I had finished my tertianship, the final stage of Jesuit training. I was asked to serve as book editor for a year, replacing Harold Gardiner, SJ, while he worked on The New Catholic Encyclopedia. So I was living at the America House Jesuit community in Manhattan in October 1963, when Walter J. Ciszek, SJ, returned to the United States after some twenty-three years in the Soviet Union—eighteen of which he spent as a prisoner, and fifteen of those years in the labor camps of Siberia. Father Ciszek had, in fact, been presumed dead, since no one, neither his family nor the Jesuits, had heard from him since 1945.

The story of his return was a sensation, picked up by the press. When his flight arrived at New York’s Idlewild (currently John F. Kennedy) Airport, television cameras were on hand along with Father Walter’s sisters and Thurston N. Davis, SJ, and Eugene Culhane, SJ, representing the New York and Maryland Jesuit Provincial Superiors.

No one knew for certain whether it would actually be Father Walter getting off the plane or some Soviet imposter, and Fathers Davis and Culhane had been Jesuit classmates of Walter’s in the 1930s before he went to Rome to study. Ciszek was ordained and then assigned to the Jesuit mission in Albertyn, Poland, to minister to Byzantine-rite Catholics there. Russian troops overran Albertyn in 1939, and that was the last anyone heard from Father Ciszek until his sisters got a letter in 1961, purportedly from him, mailed from Siberia.

Other letters followed, but his sisters could not believe it was actually Walter until he began writing about family incidents that had occurred when he was a boy and asking about other family members. Then, with the help of friends, they got in touch with the State Department to plan a trip to visit him in Russia. Instead, the State Department arranged for Father Walter to be “exchanged” for a minor Soviet “operative” who had been arrested in Washington. No one, however, knew for sure if it would actually be Walter Ciszek who got off the plane.

But it was.

Following the media circus at Idlewild, he returned with Fathers Davis and Culhane and his sisters to America House, where I first met him. That very same afternoon he went to the Jesuit novitiate in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, where he would be close to his family in Shenandoah and away from the media frenzy occasioned by his return from Russia after having been presumed dead. Everyone wanted to know his story, and Father Davis arranged with the New York and Maryland Provincials to have America magazine tell the story. To this day I have no idea why he asked me, the youngest and newest member of the staff, to write the story that was ultimately published as With God in Russia.

The very next week, after our Thursday morning editorial meeting that sent America magazine to the printer, I was on my way to Newark Airport for an afternoon flight. This was my first stop on the way to Wernersville, where I was taken to the novitiate to meet Father Ciszek.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m here to help you write your book.”

He looked at me with a blank stare. So I introduced myself and asked if he remembered meeting me at America House. He did not. Nor did he know anything about a book to be written; no one had said anything to him about it. We went for a short stroll about the grounds while I explained that I had been appointed by the editor of America to help him write his story, because everyone wanted to know about his years in Russia and the labor camps. He was polite but hardly forthcoming. He said very little himself and answered most questions with one- or two-word answers.

I finally just gave up and flew back to New York on Friday morning. I told Father Davis what happened and said, if there was a story to be told, it was not going to be told by me; I might just as well have been one of Father Ciszek’s NKVD (secret police) interrogators.

Father Davis telephoned the Maryland Provincial. No doubt the Maryland Provincial telephoned Walter. At any rate, Father Davis told me to go back to Wernersville the following Thursday and meet with Father Ciszek again. It was an entirely different situation when I arrived in Wernersville that afternoon. Walter was waiting for me at the door with a big smile and an apology and then said, “When do we start?” We started that evening after dinner in a visitors’ parlor of the rambling novitiate building.

Walter began by telling me about his childhood in Shenandoah, “because,” he said, “you’ll never understand the things I did unless you understand why I did them.” Fair enough. So he talked, and I took notes. Sometimes I asked simple questions to better understand what he was telling me, but mostly I just listened and wrote furiously. We met again Friday morning and Friday afternoon and Friday evening. And again on Saturday morning—until I said, “Enough, Walter. I can’t do any more this week.”

I flew back to New York on Sunday. Of course we had our usual weekly editorial meeting on Monday morning, and I had my usual editorial jobs to do as book editor during the week. But I was determined to finish the dictation of my Father Ciszek notes before I returned to Wernersville on Thursday afternoon, so I worked well into the night on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday dictating the Ciszek story.

That was the schedule we kept, with some exceptions, for the next six months. I flew to Wernersville on Thursday afternoons, met with Walter Thursday evening, Friday, and Saturday, then flew back to New York on Sunday. Once or twice a flight was cancelled due to weather, and Walter and I spent Thanksgiving weekend and the Christmas holidays with our respective families. But by Easter of 1964, we had pretty much completed the story that ultimately became With God in Russia.

It was not a hard story to write. Walter had a fantastic memory, and my only job was to get it down on paper. To keep the story on track and the chronology straight, I would occasionally ask some specific questions like, “What did he look like?” or “How long did that take?” or “Why did you do that?” or “What did he/you do next?” But my main tasks were to take good notes and dictate the text while it was still fresh in my mind.

I’ve learned only recently that there is a set of audio tapes in the Maryland Province archives of my weekly “interviews” with Walter. I was skeptical, because I never knew at the time that such tapes were being made. I don’t honestly know how they were made, because I don’t remember any microphones or a tape recorder in the room in which Walter and I usually met. But a copy of one of the tapes was sent to me several years ago, and it sounds rather authentic. Mysterium quoddam.

Every week one of the secretaries at America Press typed up the disks I dictated, but I didn’t bother to read the typescript myself or discuss it with Walter until we had “finished” the story. After the Easter holidays, we began to review the “chapters” serially on my weekly visits to Wernersville. At the time, Walter became concerned about using other people’s real names in the story for fear the NKVD would track down those who were still alive for questioning (or something worse). So we assigned new names to people, and I kept a list for my own purposes, just so I could keep the story straight. Walter had many corrections and additions—as the narration triggered associated memories—resulting in a “finished” manuscript that was over fifteen hundred pages.

Mr. William Holub, America’s bu

siness manager, had chosen McGraw-Hill to be the publisher of the Ciszek story after receiving proposals from a number of publishers. When I told Harold McGraw the size of the manuscript, he gasped and said we’d have to cut it to something more like five hundred pages of manuscript.

“Here’s how you do it,” he said. “Cut out all or most of the stuff about daily life in the Soviet Union, for example, what things cost, shortages, people’s attitudes, and so forth, and just assume most people already know that sort of stuff from the daily papers. Just stick strictly to the Father Ciszek story.”

So Walter and I went through the manuscript again with a hatchet. We had a lot of laughs (and a few serious arguments) over what to cut and what to leave, but we finally did get the manuscript down to something close to five hundred pages. The original fifteen-hundred-page manuscript, however, is preserved—as far as I know—in the Maryland Province archives.

Finally, as spring turned to summer in 1964, Walter came with me to America House in New York to meet with Harold McGraw and put the finishing touches on the manuscript. In the following weeks, Walter and I answered queries from the editor assigned to the manuscript by McGraw-Hill (I’ve unfortunately forgotten his name), and by July 31, the Feast of St. Ignatius Loyola, the book was sent to press.

Daniel L. Flaherty, SJ

Daniel L. Flaherty, SJ, was born in Chicago in 1929 and entered the Jesuit novitiate in Milford, Ohio, in 1947. Following his Jesuit studies at West Baden College in Indiana, he was ordained in 1963. After his time at America, Father Flaherty worked at Loyola Press as executive editor. In 1973, he was named Provincial Superior of the Chicago Province; during his tenure as Provincial he participated in the Jesuits’ 32nd General Congregation. In 1979, he was appointed director of Loyola Press and ten years later was named treasurer of the Chicago Province. He retired in 2010 and currently lives at the Colombiere Center in Clarkston, Michigan.

CHAPTER 1

The Beginnings

AN UNLIKELY PRIEST

EVER SINCE MY return to America in October 1963—after twenty-three years inside the Soviet Union, fifteen of them spent in Soviet prisons or the prison camps of Siberia—I have been asked two questions above all: “What was it like?” and “How did you manage to survive?” Because so many have asked, I have finally agreed to write this book.

But I am not much of a storyteller. Moreover, there were thousands of others who shared my hardships and survived; I have always refused to think of my experiences as something special. Out of respect for those others, I will try to set down honestly and plainly, hiding nothing and highlighting nothing, the story of those years. I will try to tell, quite simply, what it was like.

Still, I am not sure that story in itself will answer clearly the harder of those two questions, “How did you manage to survive?” To me, the answer is simple and I can say quite simply: Divine Providence. But how can I explain it?

I don’t just mean that God took care of me. I mean that He called me to, prepared me for, then protected me during those years in Siberia. I am convinced of that; but then, it is my life and I have experienced His hand at every turning. Yet I think for anyone to really understand how I managed to survive, it is necessary first of all to understand, in some small way at least, what sort of man I was and how I came to be in Russia in the first place.

I think, for instance, that you have to know I was born stubborn. Also, I was tough—not in the polite sense of the word, but in the sense our neighbors used the word those days in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, when they shook their heads and called me “a tough.” The fact is nothing to be proud of, but it shows as honestly as I know how to state it what sort of raw material God had to work with.

I was a bully, the leader of a gang, a street fighter—and most of the fights I picked on purpose, just for devilment. I had no use for school, except insofar as it had a playground where I could fight or wrestle or play sports—any sport. I refused to admit that there was anything along those lines I couldn’t do as well as—or better than—anyone else. Otherwise, as far as school was concerned, I spent so much time playing hooky that I had to repeat one whole year at St. Casimir’s parish school. Things were so bad, in fact, that while I was still in grammar school my father actually took me to the police station and insisted that they send me to reform school.

And yet my father, Martin, was the kindest of men. He was simply at his wit’s end: talking to me did no good; thrashings only gave me an opportunity to show how tough I was. And with his inherited pride and Old World belief in the family and the family name, I know that it was shame much more than anger which made him take such a step.

Both he and my mother, Mary, were of peasant stock. They had come to America from Poland in the 1890s and settled in Shenandoah where my father went to work in the mines. The family album shows pictures of him as a handsome young miner, but I remember him as a medium-sized man with thick, black hair and a glorious mustache, stocky, and, if not fat, at least not the trim young miner of those tintypes. By the time I was born, on November 4, 1904, the seventh child of thirteen, he had opened a saloon. He wasn’t the world’s best shopkeeper, though; he had too soft a spot in his heart for other newly arrived immigrants.

I don’t think my father ever really understood me. We were both too stubborn to ever really get along. He wanted me to have the education he had never had a chance to have, and my attitude left him bewildered. On the other hand, although his humiliation and shame before the police that day—as they convinced him it would be more of a family disgrace to send me away to a reform school—made a deep impression on me, I would never have admitted it to him. I had inherited too much of his Polish streak of stubbornness.

Still, he was a wonderful father. I remember the day I went to a Boy Scout outing in another town and spent the money he had given me at an amusement park near the camping grounds. I had no money for the train fare home. Instead, I hitched a ride by hanging on to the outside of one of the cars. I was nearly killed against the wall of a tunnel we passed through, and I arrived back home in Shenandoah about 1 A.M., very cold, very tired, and very scared. My father, worried, was still waiting up for me. He lit a fire in the kitchen stove and then, without waking my mother, cooked a meal for me with his own hands and saw me safely into bed. Many years later, in the Siberian prison camps, it was that episode above all others which I remembered when I thought of my father.

If it was from my father that I inherited my toughness, it was from my mother that I received my religious training. She was a small, light-haired woman, very religious herself and strict with us children. She taught us our first prayers and trained us in the faith long before we entered the parish school. Two of my sisters entered the convent, but I could never be outwardly pious. Yet it must have been through my mother’s prayers and example that I made up my mind in the eighth grade, out of a clear blue sky, that I would be a priest.

My father refused to believe it. Priests, in his eyes, were holy men of God; I was anything but that. In the end, it was my mother who finally decided the issue, as mothers often do. She told me that if I wanted to be a priest, I had to be a good one. Since my father still had doubts, I was stubborn and insisted; that September I went off to Orchard Lake, Michigan, to Sts. Cyril and Methodius Seminary, where many other young Poles from our parish had gone before me.

But I had to be different. Even though I was in a seminary, I took great pains not to be thought pious. I was openly scornful, in fact, of those who were. At night, when there was no one around, I used to sneak down to the chapel to pray—but nothing or no one could have forced me to admit it.

And I had to be tough. I’d get up at 4:30 in the morning to run 5 miles around the lake on the seminary grounds, or go swimming in November when the lake was little better than frozen. I still couldn’t stand to think that anyone could do something I couldn’t do, so one year during Lent I ate nothing but bread and water for the full forty days—another year I ate no meat at all for the whole year

—just to see if I could do it.

Yet contrary to everything we were constantly told and advised, I never asked anyone’s permission to do all this, and I told no one. When our prefect finally noticed what I was doing and warned me I might hurt my health, I told him bluntly that I knew what I was doing. Of course I didn’t; I just had a fixed idea that I would always do “the hardest thing.”

Not just physically. One summer I stayed at school during summer vacation and worked in the fields, forcing myself to bear the loneliness and the separation from family and friends. I loved baseball; I played it at school and then all summer long with the Shenandoah Indians, a hometown team that took on teams from other mining towns. I thought it would be very hard for me to give up playing the game—so, naturally, I gave it up. In my first year of college at Sts. Cyril and Methodius, I just dropped off the team. We were supposed to play an important game in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and my decision caused something of a crisis. But I was as stubborn as ever. I refused to go.

It was while I was in the seminary that I first read a life of St. Stanislaus Kostka. It impressed me tremendously. I wanted to smash most of the plaster statues that showed him with a sickly sweet look and eyes turned up to heaven; I could see plainly that Kostka was a tough, young Pole who could—and did—walk from Warsaw to Rome through all sorts of weather and show no ill effects whatsoever. He was also a stubborn young Pole who stuck to his guns despite the arguments of his family and the persecution of his brother when he wanted to join the Society of Jesus. I liked that. I thought perhaps I ought to be a Jesuit. That same year, it was a Jesuit who gave us seminarians our annual retreat. I didn’t talk to him, but I thought even more of becoming a Jesuit.

And yet I didn’t want to be one. I was due to start theology in the fall; I’d be ordained in three years. If I joined the Jesuits, it would mean at least seven more years of study. I didn’t like the idea of joining a religious order, and I especially didn’t like what I’d read about the Jesuit hallmark of “perfect obedience.” I tried to argue myself out of it all that summer. Characteristically, I asked no one’s advice. I just prayed and fought with myself—and finally decided, since it was so hard, I would do it. God must have a special Providence for hardheaded people like me.

With God in Russia

With God in Russia